|

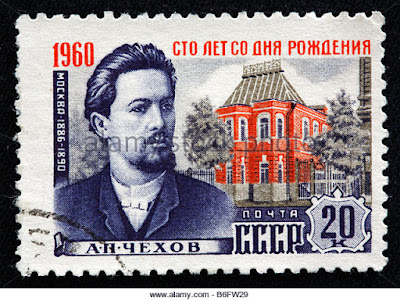

| Young Anton Chekhov, in 1882 |

THE

SCHOOLMISTRESS

AT

half-past eight they drove out of the town.

The

highroad was dry, a lovely April sun was shining warmly, but the

snow

was still lying in the ditches and in the woods. Winter, dark,

long,

and spiteful, was hardly over; spring had come all of a sudden.

But

neither the warmth nor the languid transparent woods, warmed by the

breath

of spring, nor the black flocks of birds flying over the huge

puddles

that were like lakes, nor the marvelous fathomless sky, into

which

it seemed one would have gone away so joyfully, presented anything

new

or interesting to Marya Vassilyevna who was sitting in the cart. For

thirteen

years she had been schoolmistress, and there was no reckoning

how

many times during all those years she had been to the town for her

salary;

and whether it were spring as now, or a rainy autumn evening, or

winter,

it was all the same to her, and she always--invariably--longed

for

one thing only, to get to the end of her journey as quickly as could

be.

She

felt as though she had been living in that part of the country for

ages

and ages, for a hundred years, and it seemed to her that she knew

every

stone, every tree on the road from the town to her school. Her

past

was here, her present was here, and she could imagine no other

future

than the school, the road to the town and back again, and again

the

school and again the road....

She

had got out of the habit of thinking of her past before she became

a

schoolmistress, and had almost forgotten it. She had once had a father

and

mother; they had lived in Moscow in a big flat near the Red Gate,

but

of all that life there was left in her memory only something vague

and

fluid like a dream. Her father had died when she was ten years old,

and

her mother had died soon after.... She had a brother, an officer;

at

first they used to write to each other, then her brother had given up

answering

her letters, he had got out of the way of writing. Of her old

belongings,

all that was left was a photograph of her mother, but it had

grown

dim from the dampness of the school, and now nothing could be seen

but

the hair and the eyebrows.

When

they had driven a couple of miles, old Semyon, who was driving,

turned

round and said:

“They

have caught a government clerk in the town. They have taken him

away.

The story is that with some Germans he killed Alexeyev, the Mayor,

in

Moscow.”

“Who

told you that?”

“They

were reading it in the paper, in Ivan Ionov’s tavern.”

And

again they were silent for a long time. Marya Vassilyevna thought of

her

school, of the examination that was coming soon, and of the girl and

four

boys she was sending up for it. And just as she was thinking about

the

examination, she was overtaken by a neighboring landowner called

Hanov

in a carriage with four horses, the very man who had been examiner

in

her school the year before. When he came up to her he recognized her

and

bowed.

“Good-morning,”

he said to her. “You are driving home, I suppose.”

This

Hanov, a man of forty with a listless expression and a face that

showed

signs of wear, was beginning to look old, but was still handsome

and

admired by women. He lived in his big homestead alone, and was not

in

the service; and people used to say of him that he did nothing at

home

but walk up and down the room whistling, or play chess with his

old

footman. People said, too, that he drank heavily. And indeed at the

examination

the year before the very papers he brought with him smelt of

wine

and scent. He had been dressed all in new clothes on that occasion,

and

Marya Vassilyevna thought him very attractive, and all the while

she

sat beside him she had felt embarrassed. She was accustomed to see

frigid

and sensible examiners at the school, while this one did not

remember

a single prayer, or know what to ask questions about, and

was

exceedingly courteous and delicate, giving nothing but the highest

marks.

“I

am going to visit Bakvist,” he went on, addressing Marya Vassilyevna,

“but

I am told he is not at home.”

They

turned off the highroad into a by-road to the village, Hanov

leading

the way and Semyon following. The four horses moved at a walking

pace,

with effort dragging the heavy carriage through the mud. Semyon

tacked

from side to side, keeping to the edge of the road, at one time

through

a snowdrift, at another through a pool, often jumping out of the

cart

and helping the horse. Marya Vassilyevna was still thinking

about

the school, wondering whether the arithmetic questions at the

examination

would be difficult or easy. And she felt annoyed with

the

Zemstvo board at which she had found no one the day before. How

unbusiness-like!

Here she had been asking them for the last two years

to

dismiss the watchman, who did nothing, was rude to her, and hit

the

schoolboys; but no one paid any attention. It was hard to find the

president

at the office, and when one did find him he would say with

tears

in his eyes that he hadn’t a moment to spare; the inspector

visited

the school at most once in three years, and knew nothing

whatever

about his work, as he had been in the Excise Duties Department,

and

had received the post of school inspector through influence. The

School

Council met very rarely, and there was no knowing where it met;

the

school guardian was an almost illiterate peasant, the head of

a

tanning business, unintelligent, rude, and a great friend of the

watchman’s--and

goodness knows to whom she could appeal with complaints

or

inquiries....

“He

really is handsome,” she thought, glancing at Hanov.

The

road grew worse and worse.... They drove into the wood. Here

there

was no room to turn round, the wheels sank deeply in, water

splashed

and gurgled through them, and sharp twigs struck them in the

face.

“What

a road!” said Hanov, and he laughed.

The

schoolmistress looked at him and could not understand why this queer

man

lived here. What could his money, his interesting appearance, his

refined

bearing do for him here, in this mud, in this God-forsaken,

dreary

place? He got no special advantages out of life, and here, like

Semyon,

was driving at a jog-trot on an appalling road and enduring

the

same discomforts. Why live here if one could live in Petersburg or

abroad?

And one would have thought it would be nothing for a rich man

like

him to make a good road instead of this bad one, to avoid enduring

this

misery and seeing the despair on the faces of his coachman and

Semyon;

but he only laughed, and apparently did not mind, and wanted no

better

life. He was kind, soft, naive, and he did not understand this

coarse

life, just as at the examination he did not know the prayers.

He

subscribed nothing to the schools but globes, and genuinely regarded

himself

as a useful person and a prominent worker in the cause of

popular

education. And what use were his globes here?

“Hold

on, Vassilyevna!” said Semyon.

The

cart lurched violently and was on the point of upsetting; something

heavy

rolled on to Marya Vassilyevna’s feet--it was her parcel of

purchases.

There was a steep ascent uphill through the clay; here in the

winding

ditches rivulets were gurgling. The water seemed to have gnawed

away

the road; and how could one get along here! The horses breathed

hard.

Hanov got out of his carriage and walked at the side of the road

in

his long overcoat. He was hot.

“What

a road!” he said, and laughed again. “It would soon smash up one’s

carriage.”

“Nobody

obliges you to drive about in such weather,” said Semyon

surlily.

“You should stay at home.”

“I

am dull at home, grandfather. I don’t like staying at home.”

Beside

old Semyon he looked graceful and vigorous, but yet in his walk

there

was something just perceptible which betrayed in him a being

already

touched by decay, weak, and on the road to ruin. And all at once

there

was a whiff of spirits in the wood. Marya Vassilyevna was filled

with

dread and pity for this man going to his ruin for no visible cause

or

reason, and it came into her mind that if she had been his wife or

sister

she would have devoted her whole life to saving him from ruin.

His

wife! Life was so ordered that here he was living in his great house

alone,

and she was living in a God-forsaken village alone, and yet

for

some reason the mere thought that he and she might be close to one

another

and equals seemed impossible and absurd. In reality, life was

arranged

and human relations were complicated so utterly beyond all

understanding

that when one thought about it one felt uncanny and one’s

heart

sank.

“And

it is beyond all understanding,” she thought, “why God gives

beauty,

this graciousness, and sad, sweet eyes to weak, unlucky, useless

people--why

they are so charming.”

“Here

we must turn off to the right,” said Hanov, getting into his

carriage.

“Good-by! I wish you all things good!”

And

again she thought of her pupils, of the examination, of the

watchman,

of the School Council; and when the wind brought the sound

of

the retreating carriage these thoughts were mingled with others. She

longed

to think of beautiful eyes, of love, of the happiness which would

never

be....

His

wife? It was cold in the morning, there was no one to heat the

stove,

the watchman disappeared; the children came in as soon as it

was

light, bringing in snow and mud and making a noise: it was all so

inconvenient,

so comfortless. Her abode consisted of one little room and

the

kitchen close by. Her head ached every day after her work, and

after

dinner she had heart-burn. She had to collect money from the

school-children

for wood and for the watchman, and to give it to

the

school guardian, and then to entreat him--that overfed, insolent

peasant--for

God’s sake to send her wood. And at night she dreamed of

examinations,

peasants, snowdrifts. And this life was making her grow

old

and coarse, making her ugly, angular, and awkward, as though she

were

made of lead. She was always afraid, and she would get up from

her

seat and not venture to sit down in the presence of a member of

the

Zemstvo or the school guardian. And she used formal, deferential

expressions

when she spoke of any one of them. And no one thought her

attractive,

and life was passing drearily, without affection, without

friendly

sympathy, without interesting acquaintances. How awful it would

have

been in her position if she had fallen in love!

“Hold

on, Vassilyevna!”

Again

a sharp ascent uphill....

She

had become a schoolmistress from necessity, without feeling any

vocation

for it; and she had never thought of a vocation, of serving the

cause

of enlightenment; and it always seemed to her that what was most

important

in her work was not the children, nor enlightenment, but the

examinations.

And what time had she for thinking of vocation, of serving

the

cause of enlightenment? Teachers, badly paid doctors, and their

assistants,

with their terribly hard work, have not even the comfort of

thinking

that they are serving an idea or the people, as their heads are

always

stuffed with thoughts of their daily bread, of wood for the fire,

of

bad roads, of illnesses. It is a hard-working, an uninteresting life,

and

only silent, patient cart-horses like Mary Vassilyevna could put up

with

it for long; the lively, nervous, impressionable people who talked

about

vocation and serving the idea were soon weary of it and gave up

the

work.